Decoding Climate Uncertainty

Quick Take: Don’t let uncertainty in science deter you. Rather, a goal of science is to minimize uncertainty where we can. When it comes to warming, we know enough to start making climate-aware decisions. While the physics of climate dynamics are increasingly clear, long-term societal responses remain far more uncertain.

To borrow a heuristic from Donald Rumsfeld (don’t worry, we’ll give it a good scrub before we use it), when it comes to climate change, there are known knowns, known unknowns and unknown unknowns. As climate scientists our job is to seek to move concepts and conjectures from the latter to the earlier ontologies.

Climate projections tend to find themselves in the camp of known unknowns. Their overwhelming consensus says that the world is warming at an accelerating pace, and we know roughly where and how severely. We can’t yet pin down every detail of the chronology. But that uncertainty isn’t grounds for sitting on our hands.

Research has narrowed the range of potential scenarios (and continues to do so), but we still have key challenges to address:

The speed of climate change;

The precise sensitivity of global climate to greenhouse gas concentrations;

How the impacts will manifest at a local scale;

Tipping points and other nonlinear responses to warming.

These outstanding known unknowns can be grouped into various categories of uncertainty—scientific (aleatoric and epistemic) and societal (scenario-based). Knowing which type of uncertainty you face is the first step toward making better climate-informed decisions.

The central challenge goes beyond understanding the uncertainty itself—it’s developing decision-making frameworks that can navigate each type of uncertainty we encounter:

Scientific disagreement calls for ensemble approaches embracing probability distributions, understanding that gradual trends may mask sudden shifts.

Deep uncertainty around human responses and tipping points requires robust, adaptive strategies that evolve with changing systems.

Catastrophic risks demand precautionary frameworks, especially since real-world pathways rarely follow neat scenario projections.

Effective climate decision making must grapple with dynamic systems where relationships shift over time, breakthrough innovations disrupt established patterns, and political realities create messier trajectories than any model anticipates. The goal of this article is to provide practical frameworks for decoding this complexity, recognizing that successful adaptation requires strategies that can evolve alongside our understanding of climate risk.

A Typology of Climate Uncertainty[1]

There are two types of uncertainty in the world: epistemic and aleatoric. Epistemic uncertainties are those that we seek to address through the onward march of our research. They are problems that can be solved, issues that can be addressed. Aleatoric uncertainty is the noise in any system. It is turbulence, chaos, unescapable. You can (hope to) eliminate epistemic uncertainty; aleatoric uncertainty you must live with.

Aleatoric Uncertainty: “The Noise We Can’t Escape”

Aleatoric uncertainty represents the inherent chaos in any system measurement—like your daily commute. You can never perfectly predict NYC subway timing given the everyday unpredictability of fellow passengers, weather, and train maintenance.

In climate models, aleatoric uncertainty manifests as internal variability. Patterns like El Niño or the North Atlantic Oscillation emerge from nonlinear climate dynamics, where small perturbations grow exponentially, creating deterministic chaos: this is turbulence. Internal variability is an emergent property of the nonlinear climate system; even with the most powerful climate models, we cannot perfectly predict these dynamics.

This leads climate scientists to use statistical descriptors from ensembles[2]—means and variances—rather than exact predictions. It’s like explaining, after many journeys along the same commute, that my Brooklyn-to-Midtown commute averages 32 minutes but ranges from 26 minutes on a good day to an hour when conditions align poorly. Unfortunately, it has a long tail.

Epistemic Uncertainty: “What We Can Learn”

Moving from the impossible-to-perfectly-predict to the possible-to-learn, epistemic uncertainty represents our research gaps about modelling the Earth system.

Here’s how epistemic uncertainty breaks down into cascading components:

Data Limitations: “We need more data”

Knowledge Gaps: “We don’t fully understand the relationship between any two parts of the system”

System Complexity: “The system is too complex for us to predict perfectly right now”

Each barrier appears in the modelling chain from global circulation to climate impact assessment. For example, to understand extreme heat’s impact on credit spreads, we’d ideally run regressions with hundreds of thousands of additional data points that we don’t currently possess. Nonetheless, our parameter estimates will narrow as we gather more data—this represents a simple data limitation. Knowledge gaps are different. We may not understand the functional relationship: is it linear, quadratic, or something else?

System complexity presents the broadest challenge. To truly model economic impacts, we’d need to represent supply chains, societal resilience, energy systems, and more. Our modeling choices will necessarily simplify the system’s true nature, obscuring the complete picture. However, this shouldn’t stop us from trying.

To see how these uncertainty types play out in practice, let’s examine extreme heat projections for Houston, Texas. The analysis below decomposes 40 years of climate model data to isolate what we can predict from what we cannot.

Separating Signal from Noise: Houston’s extreme heat projections show both the predictable warming trend (bottom) and irreducible year-to-year variability (top).

The two distributions in Figure 1 tell a clear story about the difference between predictable signals (epistemic uncertainty) and irreducible noise (aleatoric uncertainty). We analyzed 16 climate models projecting Houston’s extreme heat from 2015-2055. The bottom distribution (narrow blue bars) shows remarkable scientific consensus—all models agree Houston will see about 9.24 more extreme heat days per decade. This narrow spread represents epistemic uncertainty—the small disagreements between models that could shrink with better science. The top distribution (wide green spread) shows something entirely different: the year-to-year variability that remains even after accounting for the warming trend. This represents aleatoric uncertainty—the fundamental chaos in the climate system that no amount of research can eliminate.

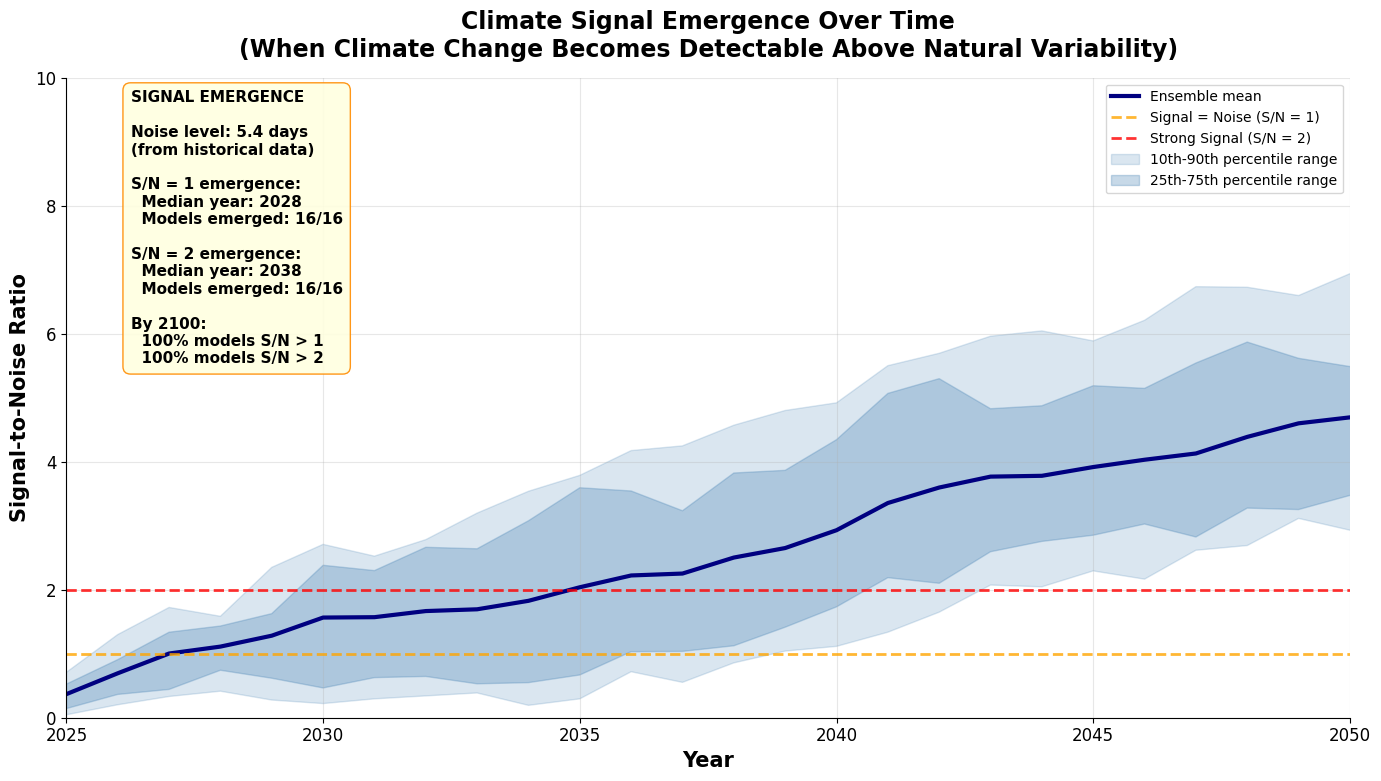

Climate signal strengthens over time: Houston’s extreme heat trend becomes 4x stronger than natural variability by 2050.

This signal-versus-noise relationship can shed additional light on how the magnitude of the original signal evolves relative to the internal variability. The question isn’t just “will it get hotter” but “when will the signal be strong enough to act on confidently? In the figure above, we model the signal-to-noise ratio which is the amount of additional heat days divided by the historical variability. By 2050, the models show an average climate signal that is greater than 4x the noise (see the figure below). While the average signal across all models crosses the strong signal threshold by 2035, only by 2045, do 90% of the models have signals at least 2x greater than the historical internal variability.

Parameter Uncertainty: Energy sector spreads climate sensitivity estimates from 1,000 model runs from 35 years of global data show directional certainty but magnitude uncertainty.

Understanding uncertainty types matters because we need to translate climate risk into impact terms. Let’s apply this framework to a concrete example: how extreme heat affects energy companies’ borrowing costs. When investors think a company is riskier, they demand higher interest rates to lend them money.

The chart above shows the uncertainty around the precise bump in rates that energy companies must pay when heat waves hit. This sort of epistemic uncertainty is parameter uncertainty. We ran the analysis 1,000 different ways, and each bar represents one possible answer. It seems that the mean coefficient is clearly in the right ballpark — extreme heat makes it more expensive for energy companies to borrow money the following year (every single estimate is positive). We’re still not sure if the true effect is small (around 7.2% change) or substantial (around 13.6% change). That’s a meaningful difference when you’re talking about billions in borrowing costs. This uncertainty isn’t like the irreducible internal variability— it’s the “we need more data” kind of uncertainty. Give us a few more years of heat waves and market data, and we’ll nail this number down with greater precision. For now, we’re confident about the direction but still learning about the magnitude. Moreover, this analysis assumes static relationships that don’t account for adaptation. Energy companies may develop heat-resilient infrastructure or financial markets may price climate risk differently as understanding evolves, introducing another layer of epistemic uncertainty.

Scenario Uncertainty: “The Human Element”

The final uncertainty category deserves special attention: societal uncertainty. Climate scientists are admittedly not philosophers or political scientists, but we do have methods for grappling with the human element—constructing scenarios that bracket plausible pathways from rapid decarbonization to continued fossil fuel dependence. While we can model climate physics with increasing accuracy, the human response remains the largest source of long-term uncertainty in our projections, combining scientific unknowns with the fundamental unpredictability of politics.

Scenario uncertainty encompasses the range of possible human responses to climate change: policy choices, technological development, behavioral changes, and collective action. Unlike physical climate processes governed by well-understood laws, human systems involve psychology, politics, economics, and culture—domains where prediction becomes extraordinarily challenging.

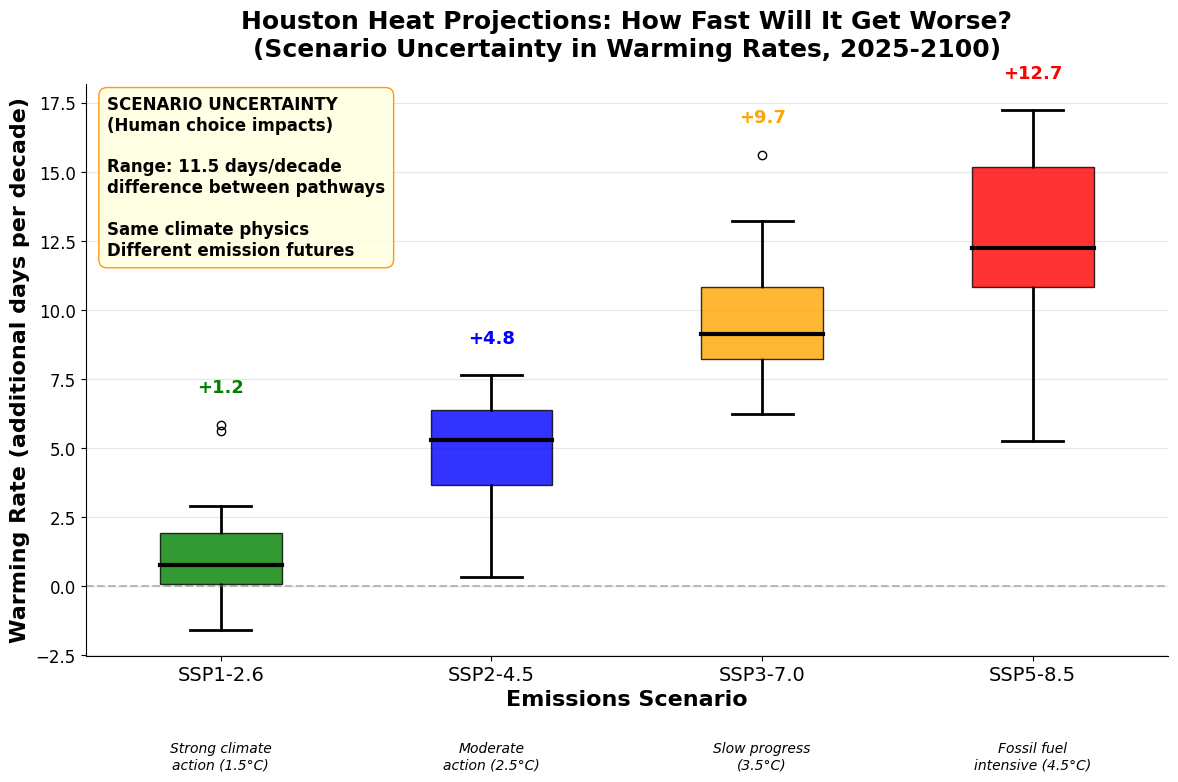

This uncertainty doesn’t diminish the importance of climate projections; rather, it emphasizes why we need comprehensive decision-making frameworks that perform well across multiple possible futures. Let’s pick it back up with Houston to get our bearings on the range of scenario uncertainty.

The chart above shows how different emission pathways create dramatically different climate futures for Houston over the next 75 years. Each box represents the same climate models running under different Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs) — standardized scenarios combining emission levels with assumptions about economic development and climate policy. The 11.5 days per decade difference between strong climate action (SSP1-2.6, green) and fossil fuel intensive futures (SSP5-8.5, red) represents pure scenario uncertainty — the range of outcomes based entirely on societal decisions, not scientific disagreement about climate physics.

The relatively narrow spread within each box shows that climate models largely agree on how the climate system responds to any given emission pathway (epistemic uncertainty is small). But the massive gaps between boxes reveal that human choices matter far more than scientific uncertainty. SSP1-2.6 assumes rapid decarbonization limiting warming to 1.5°C globally, while SSP5-8.5 represents continued fossil fuel dependence reaching 4.5°C warming. Similar climate physics, same models — the only difference is what we collectively decide to do about emissions. The science is consistent; the policy choices remain unclear.

Standardized scenarios provide useful boundaries but come with limitations. They may underestimate both technological breakthroughs and political volatility—our actual emissions trajectory often proves noisier than any neat scenario projection. Real-world pathways involve more chaotic innovation cycles and policy reversals than these smooth curves suggest.

Now, let’s compare the magnitude of these different sources of uncertainty using the examples above. We can apply energy sector credit spread coefficients to each climate model projections of extreme heat in Houston for each scenario. From there, we can pick apart which uncertainty source dominates at various time intervals within the projections.

Scenario Uncertainty Dominates Long-term: Human choices create far larger uncertainty than climate physics.

Now we can combine these analyses to determine which source of uncertainty investors should account for most, and, crucially, when. Using the Houston heat projections and energy sector sensitivity estimates, we can decompose the total risk into its component parts across different time horizons.

This analysis reveals that uncertainty sources shift dramatically over time horizons. In the near-term (2040-2050), climate model disagreement dominates at 65%. This apparent “uncertainty” masks a crucial point: the models largely agree. The range between emission scenarios (+13.9 to +24.7 additional heat days) is remarkably narrow, indicating strong scientific consensus about near-term warming regardless of emission pathway. Even the “largest” uncertainty source represents minor disagreements about the precise rate of a well-established trend. This narrow scenario range in the near-term reflects climate system inertia — the oceans and atmosphere take decades to respond fully to rising emissions.

By end-century (2090-2100), the picture transforms completely. Scenario uncertainty grows to 68% as emission pathways drive divergent outcomes: aggressive climate action yields +13.9 additional heat days while fossil fuel dependence produces +91.3 days — a 77-day difference. Climate model disagreement shrinks to 23% as emission pathways swamp scientific uncertainties. It is important to note that this is a relative decline - not necessarily an absolute decline - in uncertainty.

Crucially, both climate model and parameter uncertainties are epistemic — they represent gaps in our knowledge that will shrink as climate science advances, and we gather more financial data. Only the small aleatoric component (purple, ~3-19%) represents truly irreducible uncertainty from the climate system’s internal variability. This means that over 75% of current uncertainty could theoretically be eradicated through research, but scenario uncertainty will likely remain large due to genuine unpredictability in policy choices.

There are a few caveats to this analysis:

We ignore tipping or nonlinear elements in the climate system, another example of epistemic uncertainty. Perhaps one of most consequential unknowns about our climate system is the likelihood of catastrophic, permanent climate disruptions. For example, if the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Current collapses, no one will care about the climate risk in the energy sector. People will be in arms over global crop failure and all of Europe being frozen.

The analysis also lacks an assessment of adaptation. We assume here that the relationship between credit spreads and heat is static. This is another source of epistemic uncertainty.

The scenarios we use here are “off-the-shelf.” They represent some plausible futures but may underestimate technological innovation or political will to derail decarbonization. Our current emission trajectory seems noisier than what the scenarios provide.

Finally, we offer a few heuristics for climate decision-making, tailored to the dominant uncertainty source:

1. Short-Term Decisions (Model Uncertainty Dominates)

When climate models are your largest uncertainty source—despite their strong consensus about some aspects of climate change—embrace portfolio approaches. Diversify across the model ensemble using skill-based weights rather than equal weighting. Crucially, work with full probability distributions, not point estimates, and pay special attention to tail outcomes. The models may agree on direction, but their spread still matters for optimal allocation and risk management. I always plan for a 45-minute commute because of the long-tail, and try to ensure that my meetings start at least an hour after I plan to leave.

2. Long-Term Decisions (Scenario/Deep Uncertainty Dominates)

When facing scenario uncertainty or profound epistemic gaps about system behavior, deploy robust decision-making frameworks. Seek strategies that perform acceptably across all plausible futures rather than optimizing for any single scenario. Develop detailed storyline approaches that weave together scenario pathways, potential tipping points, and both reducible (epistemic) and irreducible (aleatoric) uncertainties. These narratives become the foundation for adaptive pathways planning—strategies that can evolve as the future unfolds and uncertainties resolve.

The meta-heuristic: match your decision framework to your uncertainty profile, recognizing that tipping points, adaptation, and scenario limitations add complexity layers that may shift which framework is most appropriate.

[1] Shepherd Theodore G. 2019 Storyline approach to the construction of regional climate change information. Proc. R. Soc. A.47520190013 http://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.2019.0013

[2] Deser, C. and Phillips, A. S.: A range of outcomes: the combined effects of internal variability and anthropogenic forcing on regional climate trends over Europe, Nonlin. Processes Geophys., 30, 63–84, https://doi.org/10.5194/npg-30-63-2023, 2023.